|

|

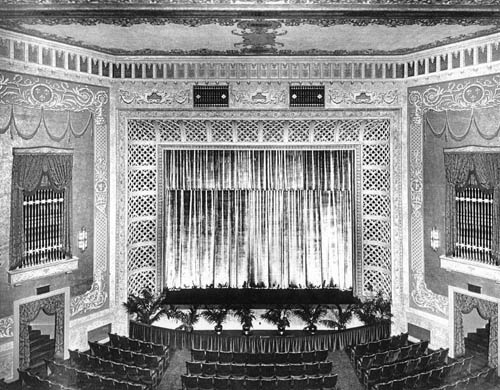

| The Rialto Theatre circa 1925 |

|

|

|

|

| Balcony View of Original Stage |

|

|

|

|

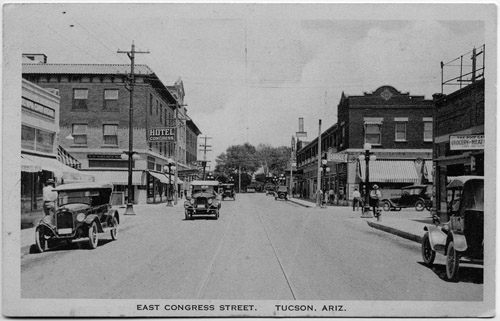

| 1920 postcard of Downtown |

|

|

|

|

| Our Screen Talks! |

|

|

A Bridge to the 14th Century After World War I, Tucson’s economy began to transform away from a natural resources and agriculture base and toward the service economy it is today. The reason? The burgeoning tourism industry. For the first time, the city began to trade on its favorable climate. And what better era in which to do so than the Roaring Twenties? Like the Hotel Congress, its sister structure across Congress Street, the Rialto was built by the California-based firm William Curlett and Son. Like all Rialtos (and there are many extant worldwide) the name hearkens to a medieval covered bridge in Venice around which novelty shops were built, providing a de facto “entertainment district” when no such thing existed. “Rialtos” were plazas where the common man could go for fun, as “Theatres” and “Operas” were reserved for the nobility and the wealthy. It’s worth noting that providing entertainment for the common man has been the ethos of the (Tucson) Rialto since its construction. The conventional wisdom in 1919 was that the two East Congress Street projects were foolhardy. It was pie-in-the-sky fantasy that Tucsonans would venture that far east, said no less an authority than the editorial board of the Tucson Citizen. But that assessment was proved incorrect in short order. Kevin Costner’s Field of Dreams sentiment “if you build it, they will come” must have been preminisced by the Curlett firm. In 1920, when the Rialto opened, motion pictures or “photoplays” didn’t predominate the theater business as they would a decade later with the arrival of “talkies” (The Rialto itself sported a lighted mini-marquee in 1930 that read “Our Screen Talks!”). The fare in most theaters at the time was vaudeville – dance, comedy, and singing – interspersed with newsreels, cartoons, and short-subject silent films, as well as the occasional feature. The first full-length film to play on the Rialto’s screen was The Toll Gate, on August 29th, 1920. Written by and starring William Hart, the film was a precursor to the type of Westerns that were frequently filmed in Tucson (although it had been shot in Sonora, California). You could say that Hart was the silent era’s Clint Eastwood, and you wouldn’t be stretching the truth that much. At the time, the Theatre possessed a majestic Kilgen pipe organ that cost $7500 (nearly $80,000 in 2004 dollars) which was later shipped to the Yuma Theater (also a Harry Nace property; see below for more) as part of the Paramount revamp. The organ’s music would accompany silent films. The lacunae left by the removal of the organ and its pipes are somewhat sad reminders of the Theatre’s earliest era. Further accompaniment and the overture that began every show came from musicians in the smallish orchestra pit that sat in front of the stage. In the beginning, city father Emanuel Drachman owned the majority interest in the Rialto. His son Royers (“Roy”) handled management duties at the Theatre for years when his father fell ill, leaving to work at another property in 1933. The Rialto had vaudeville shows every Wednesday that consisted of five different acts for the same price (“One Price House!” proclaimed some early advertisments, although that policy was later altered to put a premium on better seats). The fourth act on the bill was considered to be the star attraction and thus got the dressing room with the star on the door. This policy was somewhat altered by none other than Ginger Rogers, who was Charleston-ing her way to fame in 1925. The immensely popular dance had its roots in African-American styles and is named after the South Carolina city in which it was appropriated by whites. It was eventually supplanted by a dance called the “Black Bottom.” It is the dance from which the appellation “flapper” was derived, because practitioners appeared to be flapping their “wings.” On tour with her mother after winning a national Charleston competition held in Dallas, Rogers was booked at the Rialto but not as the fourth act. She took the dressing room with the star on the door, but when she and her mother momentarily left, the fourth act that evening commandeered it from the preening interloper. Upon their return and at her mother’s insistence, a star was added to the door of the dressing room to which Rogers had been relegated. Other noteworthy acts from the vaudeville era included prima ballerina Anna Pavlova, who was perhaps the world’s greatest ambassador of ballet in that she sought to bring her movement poetry even to small towns like Tucson; the Sistine Choir, perhaps the oldest continously extant musical group, which has served as the official papal chorus and was named after its home, the Sistine Chapel in Rome; and the Georgia Minstrels, a cultural oddity in that they were one of the few troupes in the history of minstrelsy that did not require blackface, as they were themselves black. Arizona movie theater mogul Harry Nace acquired a majority interest in the Theatre in the mid-1920s, which set the stage for its later sale to the Paramount-Publix chain, with which he had financial ties. Nace had stakes in theaters all over the state, including his flagship, the recently restored art-deco Orpheum in Phoenix, and a Rialto in Phoenix that had perhaps the best marquee of any Arizona theater, complete with a facade-spanning neon sunburst atop its giant marquee. Paramount-Publix, as the entity that would take over the Theatre in 1948 was called, was the result of an intense theater buying spree by Adolph Zukor, studio head of Paramount Pictures, in the late ‘20s. Perhaps the most controversial show in the Theatre’s history was the “All New Gay Paree” Revue in 1928. The touring company, consisting of a veritable army of 150 performers, staged a grand and for the times, bawdy showcase of singing, dancing and performance that sent ripples of titillation throughout Tucson. Posters for the revue featured a risque’ half-naked woman (read: legs and back exposed) to which community leader Reverend R.S. Beal strenuously objected, appealing to the police department to have the posters removed. Despite Beal’s machinations, and the crowd of protesters that he was able to stir up, the show indeed did go on, to huge success. The “talkie” era arrived in Tucson in the spring of 1929, in the form of the film In Old Arizona, which was billed as the first outdoor talking picture ever made. The film was based on O.Henry’s short story “The Caballero’s Way” and featured the first cinematic appearance of the classic character the Cisco Kid as its protagonist. Although much of the film takes place in Arizona, it was shot in several locations in California and Utah. The arrival of talking pictures marked the beginning of the end of the vaudeville era, as audiences found talkies so rhapsodic and spellbinding that they never looked back. In 1929, the Rialto was leased by Nace to his business associates at Paramount-Publix, which used the cinematic equivalent of the Clear Channel business model – the chain simply bought or leased every theater it could, ultimately acquiring more than 1200, and then used the leverage from that accumulation to stifle or destroy its competition. This ultimately led to a crackdown against the studio-based oligopoly that controlled theaters nationwide in the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s. Paramount-Publix invested heavily in improvements to the Rialto. It brought in new plush seating, repainted the interior (including the gaudy murals, remnants of which are still visible despite being painted over), and added swamp cooling, a new and comparatively rare treat in the scorching desert Southwest. Roy Drachman continued to manage the Theatre until 1933, during which time he witnessed both birth (a patron gave birth in his office after going into labor while at the Theatre) and death, when another attendee simply dropped dead during a screening. And even in the ‘20s and ‘30s, bouncing was a necessity, when would-be patrons would show up drunk or attempt to sneak in. Drachman went on to manage the Fox at the other end of Congress Street until 1939. A particularly grisly incident occured in the middle 1940s, when a piano player who was seated in the orchestra pit fell back against the concrete slab at the edge of the pit. His bench had collapsed, and the piano collapsed on top of him. He died from head injuries sustained in the accident. It is claimed in some quarters that his ghost still haunts the Theatre. In 1948, Harry Nace divested himself from any stake in the Theatre, and the Rialto name was changed to reflect the corporate ownership. The Theatre would be thereafter known as the Paramount for the next two decades. The old Rialto marquee came down in favor of a more modern Paramount marquee. The first film shown in the Paramount era was Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein, which was portentous in that second-run movies were later blamed for the ultimate failure of the Paramount. Interestingly enough, 1948 was also the year that the Supreme Court handed down the infamous “Paramount Decree,” which sought to end the vertical integration of movie studios and exhibition outlets. This ruling, not completely complied with until 1959, radically changed the motion picture business model and ended the oligopoly of the major studios, which included Paramount and Fox. It also did away with the scourge of blacklisting, because the studios were thereafter powerless to retaliate against the showing of blacklisted works in theaters. Some noteworthy incidents during the Paramount era included a night in 1953 with strong-enough winds to cause a wall of the Theatre to sway, shaking loose some of the clay tiles out of which the Theatre is constructed. The Paramount subsequently closed for a night to assess the structural problems and make minor repairs. In 1959, the Theatre came within days of closing due to diminished ticket sales that were the result, according to Paramount executives, of being in a “forgotten alley” – the east end of downtown. In 1962, the Paramount was robbed, leaving the coffers $1400 lighter and manager Charles E. Laughlin with a bullet in his leg. The thieves were never apprehended. The Paramount closed for good as a studio motion-picture house in 1963. According to regional ABC-Paramount (the firms had merged in the interim) supervisor Robert Reeves, who had the Theatre in his charge from 1955, there were significant problems that led to the closure – the Paramount didn’t get good, first-run films, the population core of the city was sprawling away from downtown, leaving downtown with a “graveyard feeling,” and the Theatre sat at the wrong end of a one-way street. Once the Broadway underpass closed, according to Reeves, “snowbirds,” the region’s elderly winter visitors who had consistently patronized the Theatre in prior years, were confused about how to get to there. Not so fast, said Ted Bloom of the Tucson Retail Trade Bureau. The real problem was second-run movies at the Paramount, not downtown or its configuration. In an Arizona Daily Star article which ran after the closing was announced, Bloom offered a staunch defense of downtown business, citing the number of annual downtown parking validations, among other things. “The remarks by Mr. Reeves do not make sense and show very little thought on his part. Downtown Tucson is in good shape in most areas and is not slowly dying as Mr. Reeves said. Business is good in Tucson and in downtown Tucson and prospects for the future are bright.” The Theatre’s 16 employees were let go, and the doors shuttered. Between closing in 1963 and 1971, the Theatre served perhaps its most unusual, least performance-oriented purpose: as a storage facility for Mitchell’s Furniture Gallery. Its vast interior confines served as a warehouse for the furniture retailer. The gods of theater were not amused. The Paramount lay dormant until 1971, when businessman Edward Jacobs re-opened the Theatre as El Cine Plaza – already an extant business on West Congress street but moved in to the Theatre – with new lettering to replace the Paramount blade, which read, simply, “Plaza.” El Cine Plaza was a first-run, Spanish-language movie house. However, it had strong competition from Cine Azteca, another first-run Spanish language theater that was housed in what is now the Temple of Music and Art on Scott Avenue. As a result, Jacobs turned the lease over to people who would usher in the Theatre’s most infamous era. Lessors William B. Stidham and Marion Jennings, along with Theatre manager John A. Jacobs, reopened the Theatre yet again in 1973, keeping the Plaza nomenclature. But the group had no truck with Spanish-language films. They were interested in a new business model, one that would eventually become the multi-billion dollar entity it is today: pornography. Jacobs and his group began showing the infamous film Deep Throat, starring Linda Lovelace. Naturally, great controversy was thusly engendered. The city of Tucson tried to get an injunction against the new lessors, claiming it wasn’t related to the showing of Deep Throat. It appears Stidham and Jennings had misstated some information on their application for a business license. However, the injunction was overturned, because the City had not done due diligence to make this determination before granting the license. Next at bat was the federal government, which charged manager Jacobs with receiving an obscene film in interstate commerce. He was convicted of the charge and sentenced to six months in prison and a $5,000 fine. However, his conviction was overturned by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, because the District court, in convicting Jacobs, used a definition of obscenity that did not exist when the alleged crime was committed. This ultimately led to the largely unobstructed operation of the Theatre as a porno house for five years. Amazingly enough, notorious sex performer Annie Sprinkle got her start in the blue business at the Theatre, working as a popcorn girl during showings of Deep Throat until the obscenity charge caused the Plaza to temporarily close. Sprinkle was then off to New York City, and relative fame and fortune, all due to her cervix. Beginning with Deep Throat, which was eventually seen by an estimated 54,000 people in its seven month run (an average of nearly 255 people per day!), the Theatre went on to show what are by now pornographic classics. Behind the Green Door was third, and was actually “reviewed” by Arizona Daily Star reporter Scott Carter, who now works as a producer for Real Time with Bill Maher. Also shown during this early porn era were It Happened in Hollywood, starring hirsute porn pioneers Harry Reems and Jamie Gillis, and The Devil in Miss Jones, which went on to enjoy many sequels. A memorable incident from the early ‘70s occurred as a result of the decision by Plaza management to advertise Deep Throat and other films on the doors of local taxicabs. This offended one particular woman so much she began to complain incessantly, even visiting the Theatre and having to be forcibly removed. Later, after her complaints continued to be ignored, she attempted to burn the Theatre down, either by somehow breaking in after closing or by hiding within until after it closed. She poured gasoline up the balcony stairs and over all the upper balcony seats, lit it, and escaped via the fire exit at the balcony. The fire was only hot enough to burn the seats, and after sealing the upper balcony off with plywood and framing, the Plaza reopened for business the next afternoon. The upper balcony would remain boarded up until 1993. By 1978, the business climate was once again favorable for showing Spanish-language films, mostly due to the closing of Cine Azteca at the Temple. Subsequently, the lease to Stidham and Jennings expired. Edward Jacobs’ son reopened El Cine Plaza after a bit of renovation and cleanup. Here, Spanish speaking audiences from all over Tucson would be greeted by emcee Joe Garcia on their way in to watch the exploits of Cantinflas, perhaps the most popular star of Hispanic cinema, in movies like El Diputado (“The Deputy”). Other well-loved actors included Pedro Infante, Maria Felix, and Ignacio Lopez Tarso, who starred in the well-regarded film Tarahumara. El Cine Plaza was also famous for showing double features, which exposed Spanish-speaking audiences to a new generation of performers such as Julio Iglesias in the early show. There was a minor fire in 1981 in El Cine Plaza, but the most cataclysmic event in the Theatre’s history didn’t come until January 7th, 1984. On that day, just after the start of the 6:30 screening, there was a tremendous explosion underneath the stage that could be felt blocks away. Fortunately, only one person was injured, with minor cuts. The boiler for the old Theatre had last been inspected in 1976. At some point between then and that fateful January day, someone had replaced the valve on the boiler, which was rated for 30 PSI max, with a 150 PSI max valve. The buildup in pressure was what led to the explosion, despite the early suspicion that natural gas was the cause. The destruction was extensive: the stage collapsed, as did part of the Theatre’s stagehouse; a metal door on the east side of the Theatre was blown off its hinges, and the building was subsequently condemned by the city building inspector. Fire Captain Kevin Keeley offered the opinion that the Theatre now needed very extensive renovation or a complete tear-down. What’s more, the then-manager, Jesus C. Ortiz, was cited for violations of the fire code because two exit doors were blocked, suggesting that the accident could potentially have been much more catastrophic in its human toll. All in all, it was a bad day for El Cine Plaza that fortunately wasn’t considerably worse. El Cine Plaza consequently closed its doors for good. Later in 1984, producers of the movie Desert Bloom, which starred Jon Voight, replaced the “Plaza” blade on the marquee with a blade that read “The Palace” for a scene. And the Palace it would remain until sometime in the late ‘80s when city development services forced then-owner Rich Rodgers to remove it after a civil servant noticed it being used while lit for a photo shoot, and deemed it a “public hazard.” 1984 saw another group of investors headed by Kirk Naylor purchase the Theatre, along with the apartments on the second story of the “Rialto building.” The apartments had been condemned in 1983 and the eleven senior citizens who resided in them were forced to make other arrangements. Naylor and his partners intended to return the Theatre to “the glory of the old movie houses,” and do theatrical productions as well, while simultaneously refurbishing the apartments, an impetus that rings familiar throughout this saga. Rialto Properties general manager Bill Morrissey iterated the group’s plan to turn the block into an arts and entertainment complex – a modern “rialto” – in the late ‘80s. At some point, Naylor and company deemed their ambitions unfeasible, and so by 1986 real estate mogul Rich Rodgers had acquired the Theatre, and made no bones about his intentions. About the boiler explosion, Rodgers said “It’ll take a fairly sizable infusion of funds to repair that damage,” indicating that all renovation plans, such as they were, were thereby shelved. Furthermore, Rodgers and his investment group made clear that what they’d eventually do is demolish the Theatre, making room for a parking complex to service a planned highrise complex for the east end of downtown. Rodgers, who has been accused by some quarters of “gutting” the Theatre to prepare it for demolition, claimed that the changes he made were specifically so as to be able to rent the Rialto out for the massive, multi-state Washington Public Power Supply System securities fraud trial that took place in Tucson in 1988. Rodgers painted over the entire interior and removed all the remaining fixed seating, although his plans to ultimately demolish the Theatre never came to fruition. Enter Paul Bear and Jeb Schoonover. Bear, who had founded of KXCI community radio, and Schoonover, the station’s promotions director (who also managed bands and promoted other concerts) began to make inquiries about the property, which was still owned by Rodgers. Their intent was to reopen the Theatre as the Rialto and put on concerts there, as they had at the El Casino ballroom until it closed. By late 1995 the pair had started renovation work, repaired the boiler explosion damage, and were able to open for business as a concert venue, hanging one of many different iterations of the Rialto marquee. After temporary shutdowns in early '96 and '97, Schoonover and Bear kept the Rialto in continuous operation until 2004, hosting over 700 shows from some of the best-known artists of popular music, including The Band, Black Crowes, Maroon 5, Dave Chapelle, String Cheese Incident, White Stripes, Modest Mouse, Merle Haggard, and The Roots. It's safe to say that without their intervention, there is little chance that the Rialto would still be the entertainment hub it became during their stewardship. The scrappy pair took a dilapidated and condemned building, and with a judicious use of limited resources, turned it into a renowned concert venue that was used by every promoter in the Southwest. The current Rialto era began in 2002 when former Tucson Weekly publisher Doug Biggers, along with his partnership Congress Street Investors, purchased the entirety of the Rialto block excepting the Theatre itself, which remained in Bear and Schoonover’s hands until the summer of 2004. Biggers ultimately negotiated a deal in which the city of Tucson, under the auspices of the Rio Nuevo revitalization project, purchased the Theatre and allowed funds for more extensive renovation, in turn leasing it to Biggers’ Rialto Theatre Foundation, the Rialto’s operator today. Biggers stepped down from the Foundation in 2011, with Rialto GM Curtis McCrary assuming the mantle of Executive Director in February 2012.

The first Rialto On the cusp of the Bear/Schoonover era...

|